On the first day of filming, a small crew set up in my parents’ house in Long Beach, California. We were shooting a short documentary about my parents’ experiences as Vietnam War refugees who were used as background extras in Apocalypse Now nearly 50 years ago. Though my parents played a variety of characters — translators, Viet Cong, drivers, POWs — they had no face time and no speaking parts. Director Francis Ford Coppola sought to authenticate his film by hiring Vietnamese extras. My parents were cast as background characters in a story they lived. We hoped the documentary would shift perspective, foregrounding their stories instead.

In the kitchen, I interviewed my mother. We’d always had an easy relationship. Though we had to schedule around her daily work, this part felt straightforward. It felt like every other conversation I’d ever had with my mother.

I was nervous about my father’s participation, though. While he was also open about his life, our relationship was strained. I was his adult daughter, a writer born in the US and accustomed to speaking my mind; he was a patriarch who grew enraged when I voiced opinions that didn’t match his. Our relationship was still recovering after my father said he’d disown me for a third time. Now, we said little to one another beyond hello and goodbye. My father agreed to the interview, but I wasn’t sure what would happen.

I’d primed him about what to expect, but when he returned home from work and saw the lighting and camera setup, he exclaimed in Vietnamese, “What is all this? I have nothing to say. My life isn’t important.”

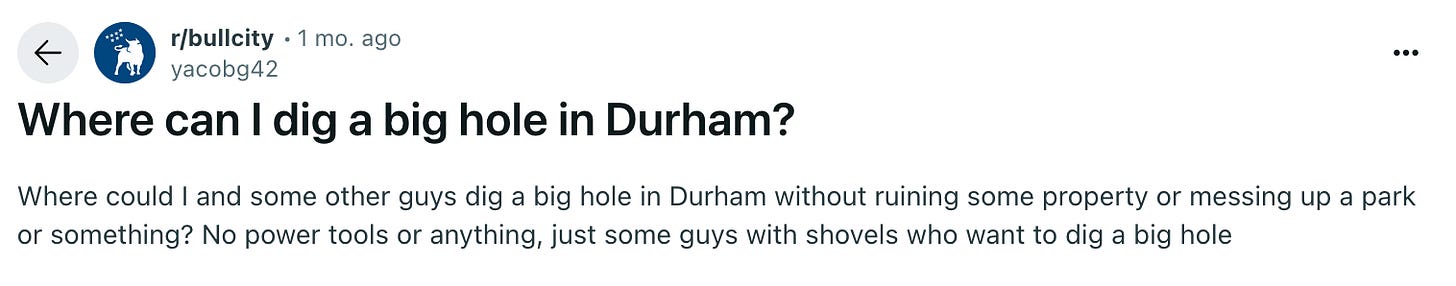

From what we knew, no video-documented first-person accounts by extras from the set of Apocalypse Now existed. We were trying to include stories of Vietnamese people who were set on the margins by this film. My father’s story was important. But how would I be able to explain this to him?

I looked nervously at the crew. I had scheduled a week for production. I’d received grant funding, flown the director and cinematographer out from New York, budgeted for food, and figured out housing. We’d already shot in Vietnam and the Philippines two months before. If my father wasn’t going to participate, how would we make our film?

My mom walked in from the kitchen and intervened: “It’s for a school project! Just go along with it.”

Inside, I chuckled. It wasn’t for a school project. I hadn’t been in school for years. But this was my mom’s way of making this project comprehensible to him.

My father nodded, still scowling, and shuffled into the bedroom to change out of his work clothes. When he emerged and spotted the crew, his demeanor changed. He might be fine challenging his family behind closed doors, but he didn’t want to appear difficult in front of others. He smiled, introducing himself, shaking hands, playing the warm host.

The sound recordist affixed mics to my parents’ shirts. My parents sat down on the living room couch. We turned on the television and played a scene from Apocalypse Now. Their narration was, at times, sad, but also funny, punctuated with laughter as they spoke about a time nearly five decades prior. I relished in my parents’ communal storytelling, the way they completed each other’s sentences. It felt like our dinner table conversation.

On the television screen, we saw two Vietnamese women shooting machine guns into the air.

Pointing at the screen, my father said, “At that time, your mother wore clothes like a…”

“…Viet Cong,” replied my mother, laughing.

My father chimed in, “She was holding an AK-47, shooting up at US helicopters!”

My mother nodded. “I was so scared. I stuffed cotton into both of my ears.”

“You know, in Vietnam, poems rhyme.”I wrote insistently about my family because the world outside of my home — the school, library, television, radio, movie theater — lacked their voices. This erasure felt painful, and I sought to make the world outside of my home my home, too. This became a focus of my art. Yet I rarely felt comfortable sharing my work with my family, especially my parents. I wrote in English; they spoke Vietnamese. And anyway, I wasn’t sure that they fully understood what I was doing as a poet, children’s book author, and now, filmmaker.

My parents vaguely understood that I was a writer. When I told my mother that I was getting an MFA in poetry, she didn’t quite understand what I was doing until I explained that the degree would allow me to teach at the university level. When my first essay was published in an issue of Poets & Writers, I showed my father a print copy of the magazine, and he declared, “Wow, that woman is so old!” The cover featured Joan Didion. When a few of my poems were translated from English into Vietnamese and published in one of the main newspapers in Vietnam, my cousin forwarded a link to my father. His only comment to me was, “You know, in Vietnam, poems rhyme.”

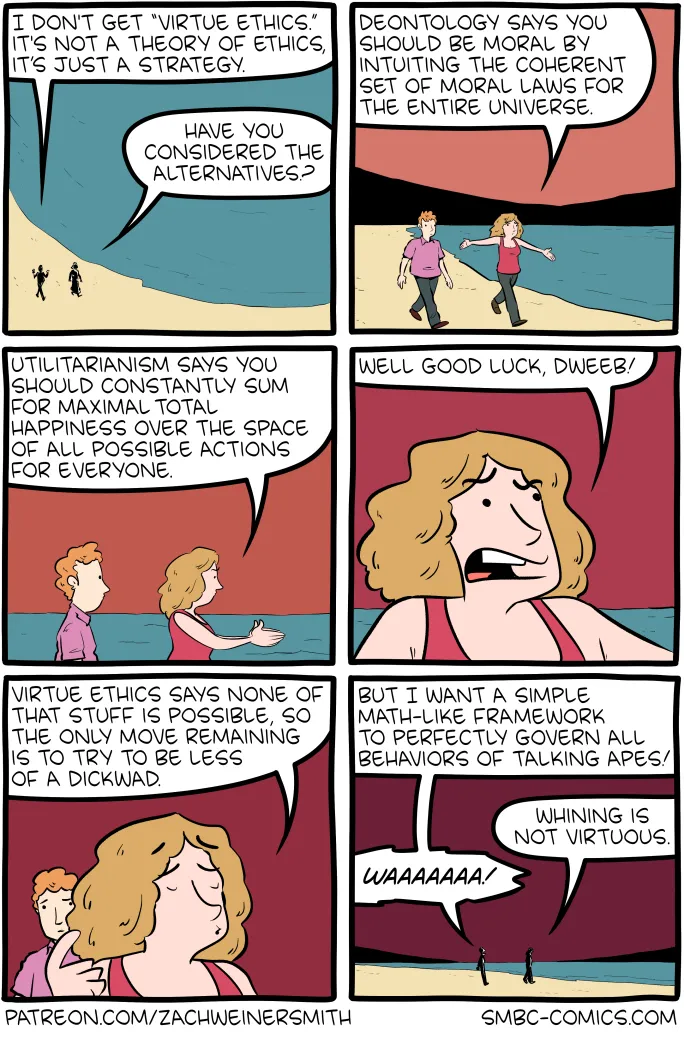

When my private writing and artmaking began to become public, I was faced with the question of bringing my ambitions into my family’s life. What seemed naturally like a process of self-definition, of carving out a space where my family was no longer being erased from the external world, was also freighted with questions about power, duty, and responsibility. Was I writing about my parents out of love, or was I extracting their stories from them to make a career in art?

Once, after I’d written about my father’s explosive anger, he told me that I had a poetic way of exaggerating the truth. “You haven’t experienced war first-hand,” he told me. “Do you know what an explosion can do?”

I didn’t. But I did know how it felt to be my father’s daughter, and I knew what it felt like to experience the war secondhand, through his stories and through him. I knew what it was like to be silenced. And I didn’t want to choose silence.

My father told me once, “You’re my daughter. Your job is to look down and say yes.” When I told him I couldn’t fulfill that role, he said, “From here on out, you’re not my daughter.” He didn’t show up for Thanksgiving that year.

Being disowned by my father was excruciating. I cried for years and felt at a loss for what to do or how to be in a world where my father, the subject of so much of my writing, wouldn’t speak to me.

For my project, I also faced a dilemma: I no longer had access to one of my main interview subjects. I’d devised this art project as a way of understanding myself and my family. Suddenly, I didn’t know how to be around him. During those years, I faced the question of what it meant to write my father’s story without him in my life.

So I wrote poems in a speculative mode, wondering, Who are we to one another when we are no longer in each other’s lives? I wrote poems in his voice, trying to understand him as a fully dimensional person. These poems would become an important braid in my collection Becoming Ghost.

Bomb that tree line back about a hundred yards. Give me room to breathe.

a golden shovel

Daughter, I think you embellish what you don’t know. A bomb

is nothing like a slammed door. That

is just your poetic imagination. Have you seen a tree

disappear into flames? That’s what a bomb can do. I taught you, line

by line, my own poetry. It was a song back

when I went hungry. Your grandmother died when I was about

to turn ten. I became an orphan then. I made sure that you never went without a

meal. I taught you to count to one hundred

in Vietnamese. You played in backyards,

on swing sets, bright shards of grass at your feet. I tried to give

you the safety I never had. And now, you tell me

that you are afraid of me? You lock yourself in your room

and write my story. I’m here, waiting to

be acknowledged. Can you hear me breathe?

For years, I continued to write about my parents’ lives as a way to understand them and our rift. Though I was deeply sad, I felt empowered to write about my parents, understanding that our stories overlapped, that I also had a right to tell these stories. Eventually, my mother stepped in and brokered a fragile peace between my father and me. It made our family gatherings less awkward, but there was still an uneasy tension in the air. We would deliberately avoid one another in order to prevent another confrontation. When I met Chris Radcliff, who would become the director and editor of the film, things between my father and me were still stiff. When Chris asked if I might consider making a documentary about my parents’ involvement in Apocalypse Now, I was taken by the idea of making a short film but anxious about what it would entail. I knew my mother would agree to it, but I was afraid of my father’s reactions.

At the dinner table, I asked my father, “Can I film you? I’m doing a project about you and mom playing extras on the set of Apocalypse Now. You’d just tell your story.”

My father shrugged and replied, “Whatever you want.”

He resumed eating. I was relieved.

Who are we to one another when we are no longer in each other’s lives?After we wrapped and completed postproduction, friends would ask what my parents thought of the film. They kept insisting that my parents must be so proud. Proud? I thought. I hadn’t considered sharing it with my parents, and I hadn’t considered the idea that my parents would ever tell me that they were proud of me.

But an editor for USA Today asked me to write up a piece about our watching the film together for the first time, and I agreed to do it.

On Christmas Day, we assembled as a family to open gifts and to eat dinner. I suggested that I screen the film. We all watched it together in the living room. While my brothers and oldest nephew were rapt and curious, my parents watched silently. I recorded their reaction on my phone. I was pleased by my brothers’ responses and waited anxiously to see what my parents would say. I couldn’t imagine them saying they were proud of me, or congratulations. But, maybe I was wrong? Maybe they’d surprise me.

Once we reached the credits, my mother clapped her hands together and said, “Okay, time for dinner!”

My parents said nothing else about the film that night. Instead, the family admired my mother’s gorgeous Christmas turkey, stuffed with sticky rice and Chinese sausage. We took photos of my mother’s achievement. She spent the evening serving others while the rest of the family ate, and we complimented her cooking for the remainder of the meal. I realized that this was my mother’s great art, not just the delicious food but the way my family gathered around it.

Eventually, we would screen the film, We Were the Scenery, at festivals to different audiences who had the chance to feel the pleasure of sitting with my parents in the living room as they told me their stories. My brothers attended the premiere at Sundance and were there when we won the short film award.

Still, that evening, it did sting a little, my parents’ total non-reaction. I had made the film to honor them, perhaps even to save them from narrative erasure. But that night, I realized that my parents didn’t feel particularly honored, and they certainly didn’t feel like they needed me to save them. Their lives were full of their own stories. For my parents, storytelling was a way for their children to understand who they are and where they came from. They participated in my interviews out of love for me. They understood their participation in my poetry and film as something that I wanted. Our storytelling has different priorities and different aims. I realized that I made the film for me and for people like me — people who felt the importance of this story in a world where it was not available.

The film didn’t have a strong effect on my parents because they didn’t need it. As we ate dinner that night, I could see that my parents didn’t feel my sense of their marginalization. They were already the stars of their own lives.