AsteroidOS 2.0 runs Linux natively on smartwatches. Here's how to port your React app to a 1.4-inch screen.

Continue reading JavaScript on Your Wrist: Porting React/Vue Apps to AsteroidOS 2.0 on SitePoint.

AsteroidOS 2.0 runs Linux natively on smartwatches. Here's how to port your React app to a 1.4-inch screen.

Continue reading JavaScript on Your Wrist: Porting React/Vue Apps to AsteroidOS 2.0 on SitePoint.

A Denver company that developed legal software tried. They failed.

A game studio that made software for Disney tried. They spent over a year and hundreds of thousands of dollars. They had a team of programmers in Armenia, overseen by an American PhD in mathematics. They failed.

Commodore Computers tried. After three months of staring at the source code, they gave up and mailed it back.

Steam looked at it once, during the Greenlight era. "Too niche," they said. "Nobody will buy it. And if they do, they'll return it."

For nearly four decades, Wall Street Raider existed as a kind of impossible object—a game so complex that its own creator barely understood parts of it, written in a programming language so primitive that professional developers couldn't decode it. The code was, in the creator's own words, "indecipherable to anyone but me."

And then, in January 2024, a 29-year-old software developer from Ohio named Ben Ward sent an email.

Michael Jenkins, 80 years old and understandably cautious after decades of failed attempts by others, was honest with him: I appreciate the enthusiasm, but I've been through this before. Others have tried—talented people with big budgets—and none of them could crack it. I'll send you the source code, but I want to be upfront: I'm not expecting miracles.

A year later, that same 29-year-old would announce on Reddit: "I am the chosen one, and the game is being remade. No ifs, ands, or buts about it."

He was joking about the "chosen one" part. Sort of.

This is the story of how Wall Street Raider—the most comprehensive financial simulator ever made—was born, nearly died, and was resurrected. It's a story about obsession, about code that takes on a life of its own, about a game that accidentally changed the careers of hundreds of people. And it's about the 50-year age gap between two developers who, despite meeting in person for the first time only via video call, would trust each other with four decades of work.

Harvard Law School, 1967

Michael Jenkins was supposed to be studying. Instead, he was filling notebooks with ideas for a board game.

Not just any board game. Jenkins wanted to build something like Monopoly, but instead of hotels and railroads, you'd buy and sell corporations. You'd issue stock. You'd execute mergers. You'd structure leveraged buyouts. The game would simulate the entire machinery of American capitalism, from hostile takeovers to tax accounting.

There was just one problem: it was impossible.

"Nobody's going to have the patience to do this," Jenkins realized as he stared at his prototype—a board covered in tiny paper stock certificates, a calculator for working out the math, sessions that stretched for hours without reaching any satisfying conclusion.

The game he wanted to make required something that didn't exist yet: a personal computer.

So Jenkins waited. He graduated from Harvard Law in 1969. He worked as an economist at a national consulting firm. He became a CPA at one of the world's largest accounting firms. He practiced tax law at a prestigious San Francisco firm, structuring billion-dollar mergers—the exact kind of transactions he dreamed of simulating in his game.

And all the while, he kept filling notebooks.

1983

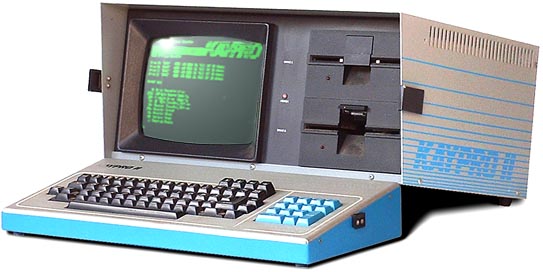

Sixteen years after those first notebooks, Jenkins finally got his hands on what he'd been waiting for: a Kaypro personal computer.

It had a screen about five inches across. It ran CP/M, an operating system that would soon be forgotten when MS-DOS arrived. It was primitive beyond belief by modern standards.

It was perfect.

Jenkins pulled out a slim booklet that came with the machine—a guide to Microsoft Basic written by Bill Gates himself. He'd never written a line of code in his life. He had no formal training in computers. But that night, he sat down and typed:

10 PRINT "HELLO" 20 END

The computer said hello.

"As soon as I did that," Jenkins later recalled, "I realized: oh, this isn't that complicated."

What happened next became the stuff of legend in the small community of Wall Street Raider devotees. Jenkins stayed up until five in the morning, writing "all kinds of crazy stuff"—fake conversations that would prank his friends when they sat down at his computer, little programs that seemed to know things about his visitors.

It was a hoot. It was also the beginning of an obsession that would consume the next four decades of his life.

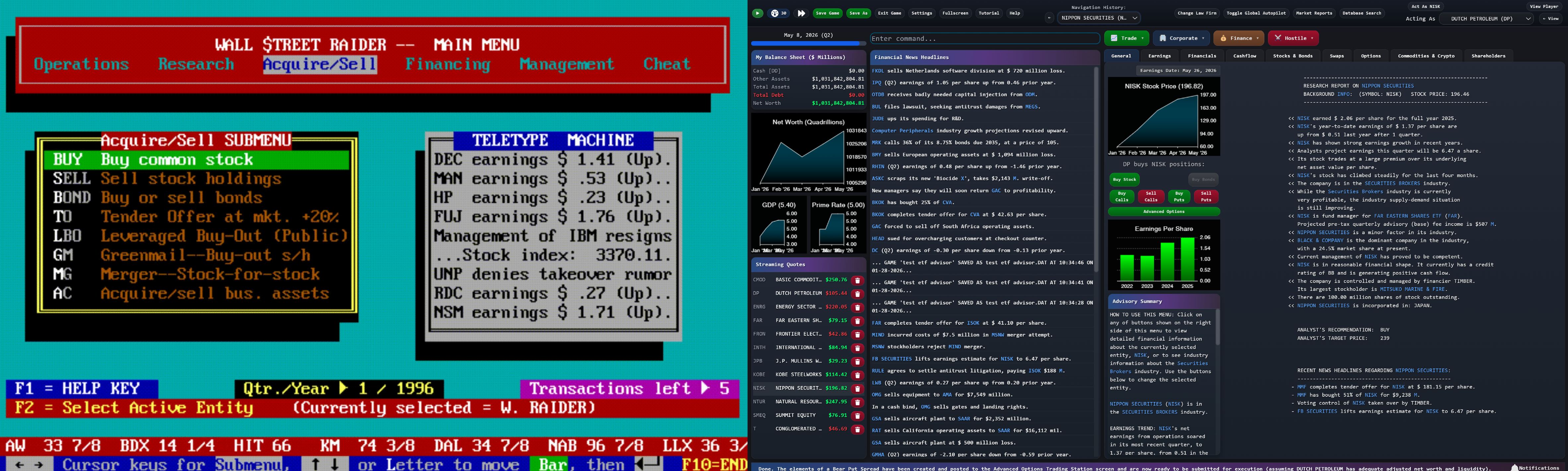

Within a year, Jenkins had built something he actually wanted: the first crude version of Wall Street Raider. It already had a moving stock ticker scrolling across that tiny five-inch screen. It already had news headlines streaming past. It was ugly and incomplete, but it was real.

Meanwhile, his law practice was suffering. "I was sitting in my office programming instead of drumming up business," he admitted. Only his side business—a series of tax guides called "Starting and Operating a Business" that would eventually sell over a million copies across all fifty states—kept him financially afloat.

The Late 1980s, 3:00 AM

The most complex parts of Wall Street Raider weren't written during normal working hours. They were written in the dead of night, in what Jenkins called "fits of rationality."

Picture this: It's three in the morning. Jenkins is hunched over his computer, trying to work out how to code a merger. Not just any merger—a merger where every party has to be dealt with correctly. Bondholders. Stockholders. Option holders. Futures positions. Interest rate swap counterparties. Proper ratios for every facet. Tax implications for every transaction.

"I felt like if I go to bed and I get up in the morning, I won't remember how to do this. So I just stayed up until I wrote that code."

— Michael Jenkins

The result? Code that worked perfectly—code that he tested for years and knew was correct—but code that even he didn't fully understand anymore.

"When I look at that code today, I still don't really quite understand it," he admitted. "But I don't want to mess with it."

This became the pattern. Jenkins would obsess over a feature until the logic crystallized in his mind, usually sometime after midnight, and then race to get it coded before the fragile understanding slipped away. The game grew layer by layer, each new feature building on the ones before, each line of code a record of what Jenkins understood about corporate finance at that particular moment in his life.

Years later, Ben Ward would give this phenomenon a name: The Jenkins Market Hypothesis.

"The hypothesis," Ward wrote in an email to Jenkins, "is that asset prices in the game reflect competition between Michael Jenkins' understanding of how Wall Street Raider worked at the point in time that he wrote the code over the past 40 years."

In other words: the game's simulated market was really just forty different versions of Michael Jenkins, from forty different stages of his life, all competing with each other.

Jenkins loved the theory. "I think it's very much related to chaos theory," he replied.

1986–2020

In 1986, Michael Jenkins retired from law and CPA practice at the age of 42. His tax guides were selling well, and his publisher had agreed to release Wall Street Raider. He thought he might spend a few years polishing his hobby project.

Thirty-four years later, he was still at it.

"I chuckle when I get emails from customers who ask me when the team is going to do one thing or the other. Well, the team is me. Ronin Software is definitely a one horse operation and always has been."

— Michael Jenkins

The game that started as a Monopoly variant had become something monstrous and magnificent. By the time Jenkins was done, Wall Street Raider contained:

Hidden beneath all this machinery was something that didn't dawn on most players until they'd been immersed in the game for months or years: an enormous amount of text. New events, scenarios, and messages would continue to pop up long after a player thought they'd seen everything—often laced with Jenkins' trademark tongue-in-cheek graveyard humor. The game wasn't just deep mechanically; it was deep narratively, in ways that only revealed themselves over time.

The game had, in short, become the most comprehensive financial simulator ever created—so complex that most people bounced off it, but those who broke through became devoted for life.

"The Dwarf Fortress of the stock market."

— what players call Wall Street Raider

Jenkins played chess against the world. He'd release a new feature, and within weeks, some clever player would email him: "Man, I found how to make trillions of dollars overnight with that new feature."

"I felt at times like the IRS plugging loopholes," Jenkins admitted. Every exploit became a patch. Every patch created new edge cases. The code grew more intricate, more layered, more incomprehensible to anyone but its creator.

And then something strange started happening.

Circa 2015

The emails started arriving from around the world, and they weren't about bugs.

One came from the Philippines:

"I've been playing your game since I was 13 years old, living in a third world country. Couldn't even afford to buy the full version. So I played the two-year demo for years and years. And it taught me so much that now I'm working for Morgan Stanley as a forex trader in Shanghai."

Another came from a hedge fund manager:

"I played Wall Street Raider for years and noticed that buying cheap companies—companies with low PE ratios—and turning them around seemed very profitable in the game. But I wasn't doing that with my real clients. I wasn't doing well. Finally I decided to just start doing what I'd been doing in Wall Street Raider."

He attached a document: an audited report from Price Waterhouse, showing a 10-year period where he'd averaged a 44% compounded annual return using strategies he'd learned from a video game.

"Your game has changed my life."

Jenkins heard it again and again. From CEOs. From investment bankers. From traders and professors and finance students. People who'd played the free demo version as teenagers in developing countries and parlayed what they learned into careers at Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. People who'd been stone masons wondering if they could do something more.

By his own count, over 200 CEOs and investment bankers had reached out over the years to say that Wall Street Raider had shaped their careers.

"I created the game because it was fun to do so," Jenkins said. "But I've been pleasantly surprised to see the positive impact it has had on the lives of a lot of people who grew up playing it for years and years."

It was, it turned out, not just a game. It was accidentally one of the most effective financial education tools ever created—a simulator so realistic that its lessons transferred directly to real markets.

Various Years

Everyone wanted to modernize Wall Street Raider. Everyone failed.

The interest was obvious. Here was a game with proven educational value, devoted fans, and gameplay depth that put most competitors to shame. The only problem was the interface—a relic of the 1990s Windows era, all dropdown menus and tiny text boxes and graphics that looked, as one longtime player put it, "like they came from the dark ages."

So they came, the would-be saviors, with their teams and their budgets and their ambitions.

A Denver company that developed legal software sent their programmers. They couldn't make it work.

A game studio that did work for Disney assembled a team in Armenia, overseen by an American PhD in mathematics. They spent over a year and "lots of money"—by some accounts, hundreds of thousands of dollars—trying to port the game to iPad.

"None of their people had the kind of in-depth knowledge of corporate finance, economics, law, and taxation that I was able to build into the game," Jenkins explained. "So they simply couldn't code the simulation correctly when they didn't have a clue how it should work."

They gave up.

Commodore Computers, back in 1990, licensed the DOS version. After three months of trying to understand the source code, they mailed it back.

Steam, during the Greenlight era, rejected it outright. "Too niche," they said. "Almost no graphics. Looks clumsy and primitive."

The pattern was always the same. Professional programmers would look at Jenkins' 115,000 lines of primitive BASIC—code that "broke all the rules for good structured programming"—and try to rewrite it in something modern. C++, usually. They'd make progress for a while, get 60% or 80% of the way there, and then hit a wall.

The problem wasn't technical skill. The problem was that to rewrite the code, you had to understand the code. And to understand the code, you had to understand corporate finance, tax law, economics, and securities regulation at the same depth as someone who'd spent decades as a CPA, tax attorney, and economist.

Those people didn't tend to become video game programmers.

"My 115,000 lines of primitive BASIC source code," Jenkins admitted, "was apparently indecipherable to anyone but me."

The skeletons piled up around the dragon.

2020–2023

By his late seventies, Michael Jenkins was running out of options.

His e-commerce provider had gone bankrupt, taking six months of income with them. Payment processors kept rejecting him—some because of obscure tax complications from selling software in hundreds of countries, others because their legal departments didn't want to be associated with anything finance-related. For a period, you literally couldn't buy Wall Street Raider anywhere.

"At one point the challenges got so overwhelming," Jenkins admitted, "that I seriously considered just shutting down everything."

In 2020, a gaming journalist named AJ Churchill sent Jenkins a simple email asking whether upgrades to Speculator (a companion game) were included in the purchase price.

Jenkins' response was... more than Churchill expected:

"Also, as a registered user, you can buy Wall Street Raider at the discounted price of $12.95. As I make revisions over a period of a year or two, I eventually decide when I've done enough that it's time to issue an upgrade version, but there is no timetable. And to be frank, I'm running out of feasible ideas for improvements to both games, and there may only be one or two more upgrades to either program.

Otherwise, at age 76, I may be finally coming near the end of development with my limited software skills, unless I can license my code to a large software/game company that is willing to hire the kind of expensive programming talent that writes software for firms like Merrill Lynch or Goldman Sachs—who would be the only programmers capable of porting my game to iOS, Android, or to a classy-looking Windows GUI. And that is very unlikely.

I've pretty much given up on the idea of anyone ever being able to port it."

Churchill posted the exchange to the r/tycoon subreddit with the title: "I reached out to the 79-year-old creator of Wall Street Raider and here's what he wrote back."

The post got some attention. People commented about what a shame it was. A few bought the game out of curiosity. And then, like most Reddit posts, it faded into obscurity.

Hear the story from Michael Jenkins and Ben Ward themselves.

But somewhere in Ohio, a young software developer read it. And he couldn't get the image of a Bloomberg terminal out of his head.

Meanwhile, in Ohio

Ben Ward's first memory of programming was going to the library as a small child and checking out a massive textbook on C++ game development.

"I barely probably knew how to read at that point," he recalled. "I had no idea how to install a compiler, run the code that was in this book. But it just kind of got me thinking."

Ward was, by his own admission, a terrible student. He had ADHD that went undiagnosed until adulthood. He spent more time helping his classmates with their homework than doing his own. His two-year programming degree took five years to complete.

But when it came to code, something clicked.

At 18, working at his uncle's manufacturing company, Ward built a management system in three months that replaced their spreadsheets. It ran the business for five years. He went on to build ERP and warehouse management systems, worked at fintech companies, and became a senior full-stack developer.

And then, just for fun, he took on a challenge: porting Colossal Cave Adventure—the legendary 1976 text adventure game—from its original Fortran code to Lua, so it could run on the Pico-8 fantasy console.

The Fortran manual was a thousand pages. Ward had never written Fortran in his life. He wrote a transpiler—a program that converts one programming language to another—and had Colossal Cave running on Pico-8 in eight hours.

"If it wasn't for that project," Ward later said, "I don't think I would have had the confidence to do this. Because of course, this was about a thousand times harder."

January 2024

Ben Ward found AJ Churchill's Reddit post while looking for stock market games to use as inspiration. He was thinking about making his own financial simulator, something with the depth he couldn't find anywhere else.

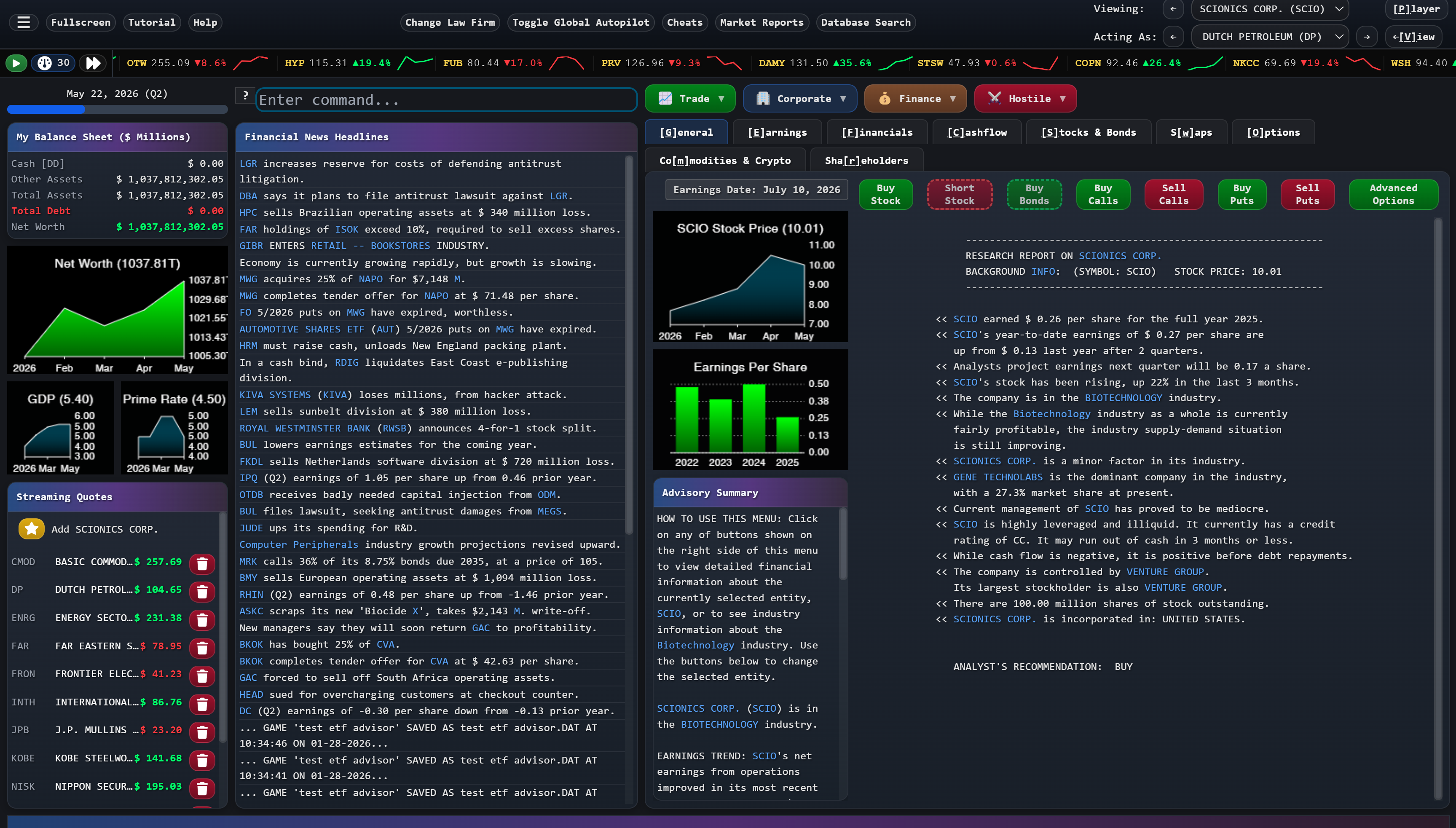

Then he discovered that the depth already existed. It just looked like it was from 1995.

Ward paid $30 for Wall Street Raider. He lost terribly for several hours. He bought the $20 manual and read all 271 pages. He was still terrible at the game.

"That's when I realized," Ward said. "This game has amazing depth. Even knowing all the rules, even memorizing all the opening moves, you still need to practice. It's like chess."

He couldn't get the image of Wall Street Raider with a Bloomberg terminal interface out of his head.

So he emailed Michael Jenkins.

Jenkins had been through this before. Over the years, developers had reached out wanting to modernize the game—promising modern graphics, mobile ports, the works. Every one of them had eventually given up. He was candid with Ward about the history:

I appreciate what you're saying, but I have to be honest—I've heard this before. A Denver legal software company tried. A Disney game studio tried. Teams of people spent hundreds of thousands of dollars and years of effort. None of them could pull it off. I'd love to be wrong, but I've learned not to get my hopes up.

Ward was persistent. Months of emails followed. Long, detailed messages about his vision, his technical approach, his background. Jenkins, cautiously optimistic, decided to give him a chance.

"Here's the source code. Let's see what you can do."

Jenkins made Ward sign an NDA—snail-mailed, because Jenkins was old school. Ward signed it, mailed it back, and received the 115,000 lines of BASIC code that represented forty years of work.

After that, the communications between them tapered off. Jenkins went back to his own work. Ward went quiet.

2024

For twelve months, Ben Ward did almost nothing but read.

He read the 2,000-page Power Basic manual. (Power Basic was the language Jenkins used—a company that was now defunct, its compiler preserved on GitHub among other places.) He re-read Wall Street Raider's 300-page game manual. He read through years of Power Basic forum posts.

"Over the course of that year," Ward estimated, "I probably spent 90% of the time reading. I wasn't really coding at all."

The feeling of failure visited him often: I'm going to be like everybody else. I can't do it. I'm not smart enough.

But Ward kept coming back to one question: Why did everyone else fail?

The Denver developers had failed. The Disney team had failed. Commodore had failed. Hundreds of thousands of dollars, gone.

"And I realized it's because they keep trying to rewrite the code," Ward said. "They keep trying to convert Power Basic to C++ or some other language, and it doesn't work."

"Don't rewrite. Layer on top."

— Ben Ward's breakthrough insight

The insight was elegant: instead of rewriting Jenkins' code, wrap a modern interface around it—the same approach enterprise companies use to modernize legacy systems every day. Keep the engine. Replace the dashboard.

After months of experimentation, Ward found a way to bridge modern code to Jenkins' untouched Power Basic engine. He tried it one day. A simple button. Some text.

It worked.

Late 2024

Ward sent Jenkins a message: a screen recording of his prototype. A button. Some text. Nothing fancy.

"This isn't anything," Ward wrote. "But this is it. Now I can use my skills to layer on top of the old engine."

Jenkins was astonished.

"When I finally reached out to Ben recently to see how he was doing, I was astonished to learn that he had spent the past year studying my code. Unlike all the other people who had tried and failed, he'd not only figured out how to overlay a new user interface onto the old framework of game logic—he'd also reworked many of the screens and just generally made the thing a lot better."

That was when everything changed.

Jenkins asked what he could do to help. Ward mentioned that the biggest bottleneck was the cryptic variable names—short abbreviations that were common in old-school programming but made the code nearly impossible to follow.

Three days later, Jenkins sent back the entire codebase with every variable renamed.

"He not only commented everything," Ward marveled, "he went through every single line of code and renamed every single variable for me in about three days. Using search and replace, because there's no IDE rename feature. And he did it flawlessly—no bugs, no side effects."

In total, Michael Jenkins and Ben Ward had two phone calls. One video call. Everything else was email.

"This guy entrusted me with 40 years of his Opus Magnum," Ward said, "all based on email."

2025

The first time Ward streamed the working game on Discord, thirty people showed up immediately.

He played his opening strategy—finding a company being sued and buying calls on the plaintiff—and made ten or twenty billion dollars in twenty minutes.

"And then I kind of just sat back," Ward recalled, "and I was like: Oh my god. It works. And it's fun."

Two years of work. Reading. Debugging. Doubting himself. And now it was real.

The Steam page went live. The open beta began. Bug reports flooded in—mostly for Ward's new code, almost never for Jenkins' battle-tested engine. Ward had done a "hostile takeover" of the dead subreddit (via Reddit's request process) and grown it from 200 users to thousands. A Discord server filled with strategy discussions and feature requests and players who'd been waiting years for this moment.

Ward, joking but not joking, posted on Reddit: "I am the chosen one, and the game is being remade."

"I mean, I was joking about 'the chosen one,'" he admitted later. But AJ Churchill, the journalist whose Reddit post had started everything, pushed back:

"Your life has led you to this moment. You worked in finance. You worked as a developer. You literally translated a game from the 1970s onto another platform. You were lab-grown to be the perfect person to work on this."

Jenkins, for his part, had found something he'd given up hoping for: someone to pass the torch to.

"I'm basically passing the Wall Street Raider torch on to Ben," Jenkins announced in a video to the community. "And I hope that its impact will endure for many more years, long after I'm gone."

Then he added a warning:

"Just one word of warning. It will take over your life."

Ward's response: "It already has. I can't escape from it now."

Michael Jenkins is 81 years old.

Will Crowther, creator of Colossal Cave Adventure—the same game Ben Ward ported to Pico-8—is 89.

"I guess that technically makes me the second oldest," Jenkins observed.

He jokes about mortality. "I plan to live forever," he says. "However, that's not too likely, I'm told."

The Wall Street Raider community jokes about it too. When Ward mentioned that release would happen "barring I don't get hit by a bus," the Discord erupted: "All bus schedules in Ohio—we're turning them off. No more buses."

Ward has taken to assuring everyone: "I look both ways when I cross the street."

Behind the jokes is something serious: the knowledge that this is Jenkins' final effort to preserve what he built. "This will be my final effort to preserve my little piece of gaming history," he said.

But Ward has built something that will outlast both of them.

"One of the reasons I wanted to put it on Steam," Ward explained, "is that let's say a freak accident happens and Michael and I both get hit by a bus. Wall Street Raider will still live on, so long as Steam doesn't take the game down. It doesn't really depend on Michael and me anymore."

2025 and Beyond

From notebooks in a Harvard Law School dormitory in 1967 to a Steam store page in 2025: fifty-eight years.

The game that almost became abandonware is now being played by thousands. The code that was "indecipherable to anyone but me" is now being extended by a new generation. The financial education that accidentally changed hundreds of careers is reaching thousands more.

5,000+ Steam Wishlists

800 Discord Members

1,000+ Reddit Community

500+ Beta Testers

200+ Players with 100+ Hours

58 Years in the Making

The remaster isn't just a new coat of paint. Ward rebuilt the entire player experience around the way financial professionals actually work: a searchable help system built on Jenkins' 271-page strategy manual, a tutorial onboarding system that's continuously being refined, contextual tooltips that walk players through the game's most advanced mechanics, and hotkeys for every button, tab, and hyperlink—just like a real Bloomberg terminal—so experienced players can move at the speed of thought.

The game underneath is still Jenkins' 115,000 lines of battle-tested code. The interface on top is what it always deserved.

The comparison that keeps coming up is Dwarf Fortress. For years, it was the same story: legendary depth, a devoted niche community, held back by an interface that scared everyone else away. When it finally got a graphical overhaul and launched on Steam in 2022, it sold over 500,000 copies in two weeks. The parallel to Wall Street Raider is hard to miss.

And then there's the story itself. An 81-year-old Harvard Law grad who taught himself to code at midnight, passing four decades of work to a 30-year-old developer from Ohio who cracked the code that no one else could. That's not a marketing angle—it's a headline that writes itself.

Jenkins still can't fully stay away. When a longtime player known as Malor kept requesting cash flow statements for banks, Jenkins insisted it would be too hard and not very useful. Two days later, he emailed Ward: "So, I think I figured out how to do cash flow statements for banks, and I've been working on this code..." Malor's handle, incidentally, is a teleportation spell from The Bard's Tale—a 1985 RPG that was the first computer game he ever saw. Wall Street Raider was the first game he installed on every new PC he ever bought. After four decades of playing, he's now in the Discord server, helping to shape the remaster he'd waited a lifetime for.

"He acts like he doesn't know how the code works," Ward observed. "But he can't stop."

Neither can the players who've been waiting for this. Neither can the new players discovering for the first time that a game this deep exists.

Wall Street Raider is, finally, getting its Bloomberg terminal interface. But underneath, it's still the same game—115,000 lines of code written by forty different versions of Michael Jenkins, competing with each other across four decades, governed by what Ward calls "laws written on top of laws that were interpreted wrong."

It's grotesquely complex. Even the creator barely understands parts of it.

And it's alive.

Recently I had to take my dog in for surgery. Over nearly 20 years of owning multiple dogs, this isn't new. But this is the first time design actually played a helpful role for my pet's post-op care.

At every other veterinary practice I've been to—over a half-dozen, from Manhattan to the rural countryside—they hand you med vials with the dosage instructions printed on them. The font on the labels is tiny (requiring reading glasses, for me) and it's impossible to read a full sentence without rotating the vial.

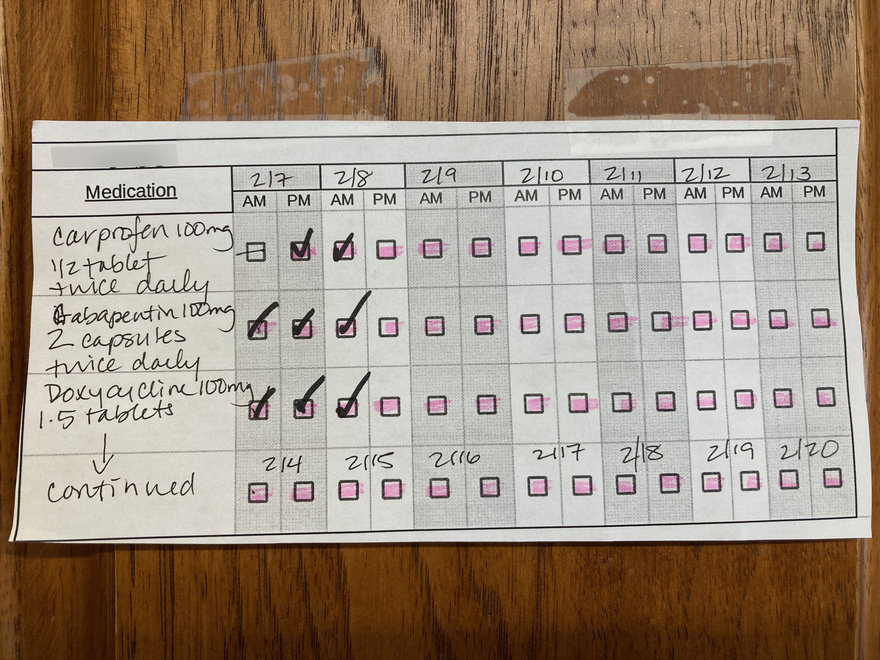

This time, however, this new vet handed me this simple chart:

I was really impressed by the low-tech efficacy of the design. The days are delineated by tonal differences, and a pink highlighter was used on all but one of the boxes, to remind me that one of the drugs was not to be administered on the morning of 2/7 (due to lingering medication from the surgery, I was verbally told). Two of the drugs are meant to be administered for 7 days in a row, and the third for 14 days in a row; the vet tech was easily able to modify the chart to indicate this.

All of this information is on the three barely-legible labels on the vials. But by consolidating it into one chart, the vet practice made the information much easier to grasp and track.

I do wonder why, having been to so many vets, this is the first time I'd seen such a chart. It should be standard practice.

If you have studied probability, you might be familiar with fractional odds, which represent the ratio of the probability something happens to the probability it doesn’t. For example, if the Seahawks have a 75% chance of winning the Super Bowl, they have a 25% chance of losing, so the ratio is 75 to 25, sometimes written 3:1 and pronounced “three to one”.

But if you search for “the odds that the Seahawks win”, you will probably get moneyline odds, also known as American odds. Right now, the moneyline odds are -240 for the Seahawks and +195 for the Patriots. If you are not familiar with this format, that means:

$100 on the Patriots and they win, you gain $195 – otherwise you lose $100.$240 on the Seahawks and they win, you gain $100 – otherwise you lose $240.If you are used to fractional odds, this format might make your head hurt. So let’s unpack it.

Suppose you think the Patriots have a 25% chance of winning. Under that assumption, we can compute the expected value of the first wager like this:

def expected_value(p, wager, payout):

return p * payout - (1-p) * wager

expected_value(p=0.25, wager=100, payout=195)

-26.25

If the Patriots actually have a 25% chance of winning, the first wager has negative expected value – so you probably don’t want to make it.

Now let’s compute the expected value of the second wager – assuming the Seahawks have a 75% chance of winning:

expected_value(p=0.75, wager=240, payout=100)

15.0

The expected value of this wager is positive, so you might want to make it – but only if you have good reason to think the Seahawks have a 75% chance of winning.

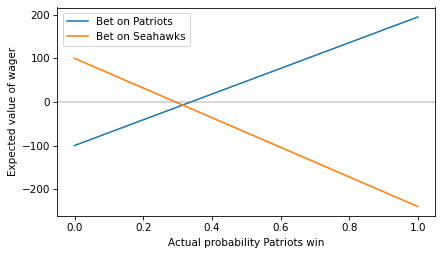

More generally, we can compute the expected value of each wager for a range of probabilities from 0 to 1.

ps = np.linspace(0, 1) ev_patriots = expected_value(ps, 100, 195)

ps = np.linspace(0, 1) ev_seahawks = expected_value(1-ps, 240, 100)

Here’s what they look like.

plt.plot(ps, ev_patriots, label='Bet on Patriots')

plt.plot(ps, ev_seahawks, label='Bet on Seahawks')

plt.axhline(0, color='gray', alpha=0.4)

decorate(xlabel='Actual probability Patriots win',

ylabel='Expected value of wager')

To find the crossover point, we can set the expected value to 0 and solve for p. This function computes the result:

def crossover(wager, payout):

return wager / (wager + payout)

Here’s crossover for a bet on the Patriots at the offered odds.

p1 = crossover(100, 195) p1

0.3389830508474576

If you think the Patriots have a probability higher than the crossover, the first bet has positive expected value.

And here’s the crossover for a bet on the Seahawks.

p2 = crossover(240, 100) p2

0.7058823529411765

If you think the Seahawks have a probability higher than this crossover, the second bet has positive expected value.

So the offered odds imply that the consensus view of the betting market is that the Patriots have a 33.9% chance of winning and the Seahawks have a 70.6% chance. But you might notice that the sum of those probabilities exceeds 1.

p1 + p2

1.0448654037886342

What does that mean?

The sum of the crossover probabilities determines “the take”, which is the share of the betting pool taken by “the house” – that is, the entity that takes the bets.

For example, suppose 1000 people take the first wager and bet $100 each on the Patriots. And 1000 people take the second wager and bet $240 on the Seahawks.

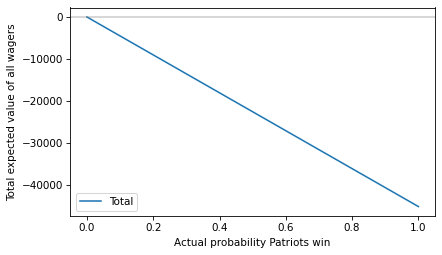

Here’s the total expected value of all of those wagers.

total = expected_value(ps, 100_000, 195_000) + expected_value(1-ps, 240_000, 100_000)

plt.plot(ps, total, label='Total')

plt.axhline(0, color='gray', alpha=0.4)

decorate(xlabel='Actual probability Patriots win',

ylabel='Total expected value of all wagers')

The total expected value is negative for all probabilities (or zero if the Patriots have no chance at all) – which means the house wins.

How much the house wins depends on the actual probability. As an example, suppose the actual probability is the midpoint of the probabilities implied by the odds:

p = (p1 + (1-p2)) / 2 p

0.31655034895314055

In that case, here’s the expected take, assuming that the implied probability is correct.

take = -expected_value(p, 100_000, 195_000) - expected_value(1-p, 240_000, 100_000) take

14244.765702891316

As a percentage of the total betting pool, it’s a little more than 4%.

take / (100_000 + 240_000)

0.04189636971438623

Which we could have approximated by computing the “overround”, which is the amount that the sum of the implied probabilities exceeds 1.

(p1 + p2) - 1

0.04486540378863424

In summary, here are the reasons you should not bet on the Super Bowl:

Betting is a zero-sum game if you include the house and a negative-sum game for people who bet. If you make money, someone else loses – there is no net creation of economic value.

So, if you have the skills to beat the odds, find something more productive to do.

The post Don’t Bet on the Super Bowl appeared first on Probably Overthinking It.

In the early 20th century, scientists sought to get to the bottom of a mysterious disease that caused thousands of deaths per year in the United States. By 1912 in South Carolina alone, more than 30,000 cases were reported with a fatality rate of 40 percent.

This ailment is known as pellagra, and it was discovered as early as the 18th century when it inflicted Spanish peasants. At the time, it was commonly confused with leprosy as it can cause skin sores. The condition also triggers symptoms throughout the body including diarrhea, neurological issues like tremors, and even dementia. In 1869, Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso suggested that pellagra comes from spoiled corn, as it often affects people with corn-heavy diets.

Lombroso’s theory entered the conversation when pellagra became epidemic throughout the Southern U.S. Some eugenicists suggested that it stemmed from racial or hereditary factors. A 1912 investigation of a South Carolina mill village reported that the disease was infectious, a finding that guided doctors for years.

Around this time, Congress asked the Surgeon General to investigate pellagra. He tapped Joseph Goldberger, a medical officer in the U.S. Public Health Service, to take the reins. Goldberger was already recognized for his work on epidemics such as typhus and yellow fever.

Goldberger suspected that the disease was linked to a diet lacking key nutrients, not infection—a possibility also raised by researchers in Europe. In the early 20th century, low-income people in the South mostly ate cornmeal, meat, and molasses. Due to the region’s thriving cotton industry, little land remained to grow vegetables.

It was already known that wealthy people were far less likely to develop pellagra, and Goldberger had observed the condition among patients and residents at the mental hospitals and orphanages he visited, yet not the staff.

Following his intuition, he carried out an experiment on male inmates at a Mississippi prison that began on this day in 1915. These men received pardons for their participation, an unethical exchange that wouldn’t be approved today. He observed how they fared on their usual diet, which included dairy products and vegetables grown at the farm they worked at, versus a typical Southern diet at the time. Eleven subjects stayed on this diet until late October 1915, six of whom experienced pellagra symptoms. “I have been through a thousand hells,” one participant remarked. All of these individuals eventually recovered.

Read more: “Fruits and Vegetables Are Trying to Kill You”

Goldberger had also studied populations at orphanages and asylums in the South, and came to the conclusion that an unbalanced diet can trigger pellagra. In fact, some asylum patients with dementia saw such drastic improvements on an improved diet that they were discharged.

Still, Goldberger’s advice mostly went unheeded. Southern politicians and doctors tended to reject his theory linking the condition to poverty in their region, insisting pellagra was an infectious disease or that it stemmed from moldy corn. This prompted Goldberger to organize “filth parties,” where people took pills containing skin, urine, and other samples taken from individuals with pellagra, yet attendees didn’t go on to develop the condition.

Despite Goldberger’s breakthroughs, he couldn’t pinpoint the exact ingredient required to prevent pellagra. In 1927, he found that a daily dose of brewer’s yeast offered an effective treatment, and a year later he asserted that pellagra likely results from a vitamin deficiency. The next year, though, pellagra reached its peak in the South and killed nearly 7,000 people.

Before Goldberger could get to the bottom of it, he died from kidney cancer in 1929. But less than a decade later, scientists landed on that specific vitamin: niacin. Biochemist Conrad Elvehjem arrived at this discovery after administering small amounts of niacin to dogs with the canine equivalent of pellagra, and the treatment ended up working for humans, too. Corn does contain niacin, but in a form that our bodies can’t absorb well—Indigenous people in the Americas have rendered niacin easier to digest for centuries by soaking corn kernels in limewater.

Today, pellagra is rare in many countries thanks to flour fortified with niacin, a practice that ramped up in the U.S. during World War II. It’s considered a massive public health success story, effectively wiping out one of the most devastating nutritional deficiency diseases ever documented in the country. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: hartono subagio / Pixabay

1 year ago (Jan 2025) I quit my job as a software engineer to launch my first hardware product, Brighter, the world’s brightest lamp. In March, after $400k in sales through our crowdfunding campaign, I had to figure out how to manufacture 500 units for our first batch. I had no prior experience in hardware; I was counting on being able to pick it up quickly with the help of a couple of mechanical/electrical/firmware engineers.

The problems began immediately. I sent our prototype to a testing lab to verify the brightness and various colorimetry metrics. The tagline of Brighter was it’s 50,000 lumens — 25x brighter than a normal lamp. Instead, despite our planning & calculations, it tested at 39,000 lumens causing me to panic (just a little).

So with all hands on deck, in a couple of weeks we increased the power by 20%, redesigned the electronics to handle more LEDs, increased the size of the heatsink to dissipate the extra power, and improved the transmission of light through the diffuser.

This time, we overshot to 60,000 lumens but I’m not complaining.

Confident in our new design I gave the go ahead to our main contract manufacturer in China to start production of mechanical parts. The heatsink had the longest lead time as it required a massive two ton die casting mold machined over the course of weeks. I planned my first trip to China for when the process would finish.

Simultaneously in April, Trump announced “Liberation Day” tariffs, taking the tariff rate for the lamp to 50%, promptly climbing to 100% then 150% with the ensuing trade war. That was the worst period of my life; I would go to bed literally shaking with stress. In my opinion, Not Cool!

I was advised to press forward with manufacturing because 150% is bonkers and will have to go down. So 2 months later in Zhongshan, China, I’m staring at a heatsink that looks completely fucked. Due to a miscommunication with the factory, the injection pins were moved inside the heatsink fins, causing the cylindrical extrusions below. I was just glad at least the factory existed.

I returned in August to test the full assembly with the now correct heatsink. At my electronics factory as soon as we connect all the wiring, we notice the controls are completely unresponsive. By Murphy’s Law (anything that can go wrong will go wrong), I had expected something like this to happen, so I made sure to visit the factory at 10am China Standard time, allowing me to coordinate with my electrical engineer at 9pm ET and my firmware engineer at 7:30am IST. We’re measuring voltages across every part of the lamp and none of it makes sense. I postpone my next supplier visit a couple days so I can get this sorted out. At the end of the day, we finally notice the labels on two PCB pins were swapped.

With a functional fully assembled lamp, we OK mass production of the electronics.

Our first full pieces from the production line come out mid October. I airship them to San Francisco, and hand deliver to our first customers. The rest are scheduled for container loading end of October.

Early customers give some good reviews:

People like the light! A big SF startup orders a lot more. However, there is one issue I hear multiple times: the knobs are scraping and feel horrible. With days until the 500 units are loaded into the container, I frantically call with the engineering team and factory. Obviously this shouldn’t be happening, we designed a gap between the knobs and the wall to spin freely. After rounds of back and forth and measurements, we figure out in the design for manufacturing (DFM) process, the drawings the CNC sub-supplier received did not have the label for spacing between the knobs, resulting in a 0.5mm larger distance than intended. Especially combined with the white powder coating which was thicker than the black finish, this caused some knobs to scrape.

Miraculously, within the remaining days before shipment, the factory remakes & powder coats 1000 new knobs that are 1mm smaller in diameter.

The factory sends me photos of the container being loaded. I have 3 weeks until the lamps arrive in the US — I enjoy the time without last minute engineering problems, albeit knowing inevitably problems will appear again when customers start getting their lamps.

The lamps are processed by our warehouse Monday, Dec 12th, and shipped out directly to customers via UPS. Starting Wednesday, around ~100 lamps are getting delivered every day. I wake up to 25 customer support emails and by the time I’m done answering them, I get 25 more. The primary issue people have is the bottom wires are too short compared to the tubes.

It was at this point I truly began to appreciate Murphy’s law. In my case, anything not precisely specified and tested would without fail go wrong and bite me in the ass. Although we had specified the total length of the cable, we didn’t define the length of cable protruding from the base. As such, some assembly workers in the factory put far too much wire in the base of the lamp, not leaving enough for it to be assembled. Luckily customers were able to fix this by unscrewing the base, but far from an ideal experience.

There were other instances of quality control where I laughed at the absurdity: the lamp comes with a sheet of glass that goes over the LEDs, and a screwdriver & screws to attach it. For one customer, the screwdriver completely broke. (First time in my life I’ve seen a broken screwdriver…) For others, it came dull. The screwdriver sub supplier also shipped us two different types of screws, some of which were perfect, and others which were countersunk and consequently too short to be actually screwed in.

Coming from software, the most planning you’re exposed to is linear tickets, sprints, and setting OKRs. If you missed a deadline, it’s often because you re-prioritized, so no harm done.

In hardware, the development lifecycle of a product is many months. If you mess up tooling, or mass produce a part incorrectly, or just sub-optimally plan, you set back the timeline appreciably and there’s nothing you can do but curse yourself. I found myself reaching for more “old school” planning tools like Gantt charts, and also building my own tools. Make sure you have every step of the process accounted for. Assume you’ll go through many iterations of the same part; double your timelines.

In software, budgeting is fairly lax, especially in the VC funded startup space where all you need to know is your runway (mainly calculated from your employee salaries and cloud costs).

With [profitable] hardware businesses, your margin for error is much lower. Literally, your gross margin is lower! If you sell out because you miss a shipment or don’t forecast demand correctly, you lose revenue. If you mis-time your inventory buying, your bank account can easily go negative. Accounting is a must, and the more detailed the better. Spreadsheets are your best friend. The funding model is also much different: instead of relying heavily on equity, most growth is debt-financed. You have real liabilities!

Anything that can go wrong will go wrong. Anything you don’t specify will fail to meet the implicit specification. Any project or component not actively pushed will stall. At previous (software) companies I’ve worked at, if someone followed up on a task, I took it to mean the task was off track and somebody was to blame. With a hardware product, there are a million balls in the air and you need to keep track of all of them. Though somewhat annoying, constant checkins simply math-out to be necessary. The cost of failure or delays is too high. Nowadays as a container gets closer to shipment date, I have daily calls with my factories. I found myself agreeing with a lot of Ben Kuhn’s blog post on running major projects (his blog post on lighting was also a major inspiration for the product).

When I worked at Meta, every PR had to be accompanied with a test plan. I took that philosophy to Brighter, trying to rigorously test the outcomes we were aiming for (thermals, lumens, power, etc…), but I still encountered surprising failures. In software if you have coverage for a code path, you can feel pretty confident about it. Unfortunately hardware is almost the opposite of repeatable. Blink and you’ll get a different measurement. I’m not an expert, but at this point I’ve accepted the only way to get a semblance of confidence for my metrics is testing on multiple units in different environments.

As someone who generally stays out of politics, I didn’t know much about the incoming administration’s stance towards tariffs, though I don’t think anyone could have predicted such drastic hikes. Regardless, it’s something you should be acutely aware of; take it into consideration when deciding what country to manufacture in, make sure it’s in your financial models with room to spare, etc…

I wish I had visited my suppliers much earlier, back when we were still prototyping with them. Price shouldn’t be an issue — a trip to China is going to be trivially cheap compared to buying inventory, even more so compared to messing up a manufacturing run due to miscommunication. Most suppliers don’t get international visitors often, especially Americans. Appearing in person conveys seriousness, and I found it greatly improved communication basically immediately after my first visit. Plus China is very different from the US and it’s cool to see!

To me, this process has felt like an exercise in making mistakes and learning painful lessons. However, I think I did do a couple of key things right:

The first thing I did before starting manufacturing—and even before the crowdfunding campaign—was setting up a simple website where people could pay $10 to get a steep discount off the MSRP. Before I committed time and money, I needed to know this would be self-sustaining from the get go. It turns out that people were happy to give their email and put down a deposit, even when the only product photos I had were from a render artist on fiverr!

From talking to other hardware founders, these kinds of mistakes happen to everyone; hardware is hard as they say. It’s important to have a healthy enough business model to stomach these mistakes and still be able to grow.

Coolest Cooler had an incredibly successful crowdfunding campaign, partly because they packed a lot of features into a very attractively priced product. Unfortunately, it was too attractively priced, and partway through manufacturing they realized they didn’t have enough money to actually deliver all the units, leading to a slow and painful bankruptcy.

When the first 500 units were being delivered, I knew there were bound to be issues. For that first week, I was literally chronically on my gmail. I would try to respond to every customer support issue within 1-2 minutes if possible (it was not conducive to my sleep that many of our customers were in the EU).

Some customers still had some issues with the control tube knobs & firmware. I acknowledged that they were subpar and decided to re-make the full batch of control tubes properly (with the correct knob spacing), as well as updated firmware & other improvements, and ship them to customers free of charge.

Overall, it’s been a very different but incredibly rewarding experience compared to working as a software engineer. It’s so cool to see something I built in my friends houses, and equally cool when people leave completely unprompted reviews: